Tambo colorado: City of Color

Texto y fotos Carlos Gómez

The world is color and the native people of Perú’s central coast understood this very well. Colors produce sensations, feelings, and moods, express values and situations, and transmit messages and symbols. Perhaps this the symbolic content of Tambo Colorado, the mythical city of the Tahuantinsuyo Empire, in the fertile and picturesque Pisco River Valley gorge, in the district of Humay.

As I travel along the twenty-five mile stretch of the Los Libertadores Highway, from the town of San Clemente to my destination, I enjoy the fruit orchards and fields of cotton, corn, and other staples. Outside the bus window I observe the palette of greens in this valley, farmed with care for many uses, in keeping with ethical and environmental principles founded on an intimate relationship with nature. Looking at the crops, I think about traditional cultural practices and the devotion to work and love of the land of these indigenous people who refuse to simply use up the planet.

I’m on my way to Pucallacta, or Pucahuasi (both from the Quechua word “puka,” meaning red), the original names for Tambo Colorado. I arrive in the morning, under a blazing sun that remains present much of the year, and come across a sign that reads “National Culture Institute, Tambo Colorado. Archaeological Zone.”

A blue sky sets off the green valley and brightens the colors of the ruins. My tour guide, José, a humble, educated man with cheeks chapped by the wind and sun, tells me that this site was built around 1450 on a former Chincha stronghold. The great Inca Tupac Yupanqui transformed the ancient city and used it to monitor the traffic between the coast and the mountains while building the empire.

The colorful complex reveals an ordered approach to space, constructions with smaller chambers for bedrooms, open communal spaces, storehouses, a large section of the valley reserved for growing food, and a road connecting the coast with Cuzco, the heart of the Inca Empire.

The uniqueness of this adobe complex lies in the way the Incas adapted and transformed the architectural style typical of the mountains—finely carved, superimposed blocks of stone covered in mud and adobe designs— with Tambo Colorado’s red, yellow, and white walls and façades. It is an example of the way the Incan architects adapted to the new coastal environment they were beginning to dominate and subdue.

This political-administrative center functioned as a control zone between the mountains and the coast and included a military base, lodgings for the Inca, a rest area, a ceremonial site, food storehouses, and a meeting point. The enclave, witness to one of the continent’s golden ages, is the best preserved of the many settlements and structures built by the Incas during their expansion along the Peruvian coast.

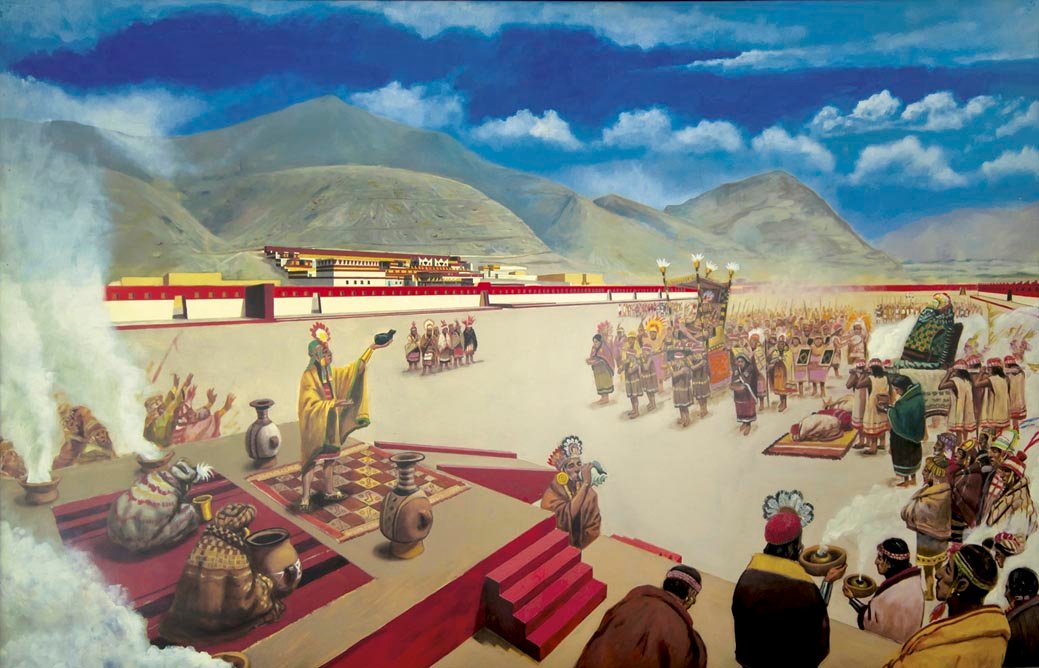

The urban complex is comprised of three large areas: the central, northern, and southern sectors, all united by the Inca road system. The central sector connects the north and south by way of a large trapezoidal plaza with an “ushnu,” or small pyramidal platform. The platform provides a clear view of the broad, diverse valley winding towards the Pacific Ocean, where the Spanish conquerors entered. The ushnu, protected on either side by the mountains that form the valley, lent a sacred air to the Tahuantinsuyo’s most important ceremonies and festivities, which were directed by the Inca or his direct representative. I feel the energy here in this ritual space; the breeze and birdsong make it possible to imagine the footsteps of the people who imprinted their own identity on the new political and social order of the empire by using color in their constructions.

José opens an ancient padlock on a small wooden door leading to the northern sector, which is nestled against the mountainside. I’m surprised by how showy it is: definitely reserved for the elite. Known as the Temple of the Sun or the Monastery of the Solar Virgins, it was used by the Inca, or his representative and court, when he was passing through the valley. A large building with dual-jamb trapezoidal niches and a single entrance towers overhead. These elements are characteristic of important buildings in places such as Machu Picchu and Koricancha. In the brisk, whistling wind I walk slowly along the 330-foot facade and the adjoining 500-foot central courtyard, surrounded by more than thirty rooms in a single enclosure with trellises overhead and straight-angled, inclined walls adorned with mud carvings like clay friezes. Another characteristic feature is the trapezoidal niches of different sizes looking out on the surrounding mountains where the Apus, or guardian spirits dwelled.

The guide points out that the interior floor plan and chambers in the Tambo Colorado Palace reveal a marked spatial hierarchy. He tells me that the restricted labyrinthine access down long, narrow passageways, patios, and double jamb doorways is unique. And the red, yellow, and white coloring works together with the building’s dimensions and spatial organization to denote the status of those who entered the different parts of the building.

I ask about the patterns of the overlapping horizontal bands of color and the guide tells me they were not always the same. At different moments throughout the Inca rule, many of the walls were repainted and the pattern of the previous color was not always respected. One of the most remarkable modifications was the sophisticated wall decoration with colorful triangles covered with a layer of plaster painted white, visible in only a few places.

The southern sector is less showy and consists of two rectangular buildings with a dividing wall between them. Both buildings are arranged around a courtyard with numerous enclosures. Along the inner trapezoidal square stand structures used as dwellings or storehouses, and a main building known as La Fortaleza, or The Fort. The enclosures in this city of color are differentiated by the purpose they served; some were used as permanent dwellings for officials, others were reserved for powerful visitors, military officials, and the chasquis, young messengers trained from childhood to run the length of the far-reaching Inca roads, carrying valuable information used to control the empire through a relay system.

I finish my tour in front of maps and models that illustrate the site’s dimensions, and objects collected during archaeological excavations. Five hundred years after Vasco Nunez de Balboa’s sighting of the Pacific Ocean and the Spanish occupation, there is still much to learn about the lifestyles of those who inhabited this city of color. The many interpretations and meanings attributed to its painted walls continue to inspire both admiration and questions. Why not visit for yourself?